FlexObject (InDesign 2026) on the Scripting Side

November 07, 2025 | Tips | en | fr

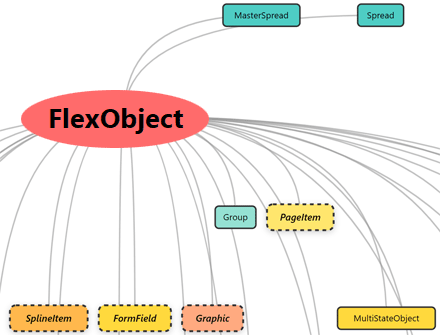

The introduction of Flex Layout in InDesign 2026 represents a significant evolution in the scripting DOM architecture. Unlike traditional container objects, FlexObject entities operate at the same hierarchical level as fundamental layout containers (Spread and MasterSpread) while exhibiting behavioral patterns similar to Group and MultiStateObject, but with dynamic layout capabilities inspired by CSS Flexbox.

While FlexObject implements the abstract PageItem interface (as evidenced by its shared API including geometricBounds, transform, and all common PageItem properties), it operates at a strategic level equivalent to Group and MultiStateObject in the containment hierarchy. As the InDesign SDK states, a page item represents “content the user creates and edits on a spread”—and FlexObject qualifies as such content, just like Groups, TextFrames, and many other components. The fact that Document, Spread, and Page objects now expose a flexObjects collection property—parallel to existing collections like pageItems, groups, and multiStateObjects—confirms FlexObject's status as a first-class container.

Parent-Child Relationships

As a parent, FlexObject can contain 30+ distinct object types, including all PageItem instances (any object that implements the PageItem interface), that is: SplineItems (Polygon, Rectangle, Oval, GraphicLine…), form fields and HtmlItems (CheckBox, ComboBox, ListBox, RadioButton, TextBox, SignatureField…), MediaItems (Sound, Movie) and SVG, text frames (TextFrame, EndnoteTextFrame), composite objects (Group, MultiStateObject, Button), not to mention settings and preferences (AnimationSetting, TransparencySetting family, TextWrapPreference, and so on.)

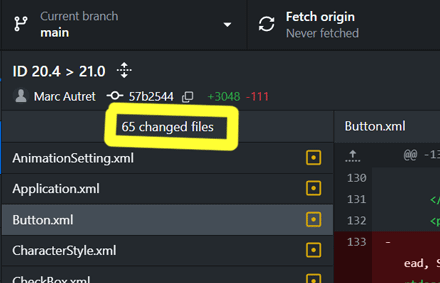

As shown in the “aerial view” screenshot above (made from a Git diff of DOM's XML data), the penetration rate of the FlexObject class throughout the architecture is very high. 65 classes were modified between InDesign 20 and InDesign 21, and most of these changes directly concern Flex Layout.

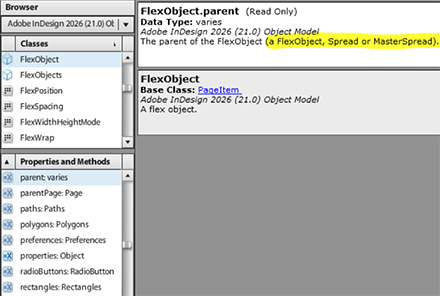

Now, if we blindly refer to the official API documentation, FlexObject could only be contained by three parent types: Spread, MasterSpread, and FlexObject (enabling nested flex layouts). This asymmetric pattern is intended to reveal FlexObject's dual nature: behaving as a high-level container (at the Spread level) while maintaining PageItem-like flexibility (in what is contained).

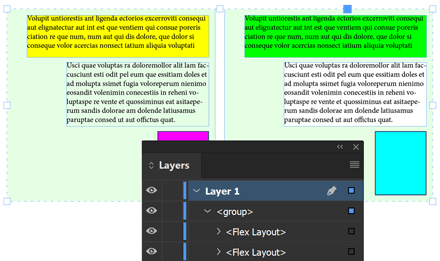

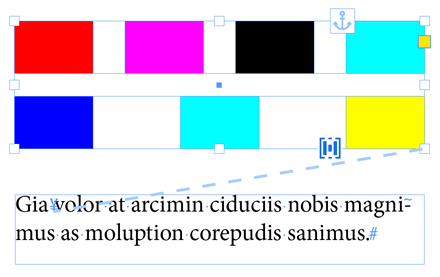

That is at least what the property explorer says (shown above in the ESTK). But it's easy to verify, in InDesign, that this restriction doesn't apply at all. For example, you can easily group two FlexObjects:

As a result, each FlexObject will have the Group in question as its parent property. I haven't tested this kind of hybrid configuration in more depth, but given that the flexObjects collection is exposed in all objects of the PageItem type and even sub-type (including the most specific ones), there is every reason to consider that in fact, a FlexObject can virtually belong to any type of parent in the craziest nesting!

Note. — However, there are certain limitations specific to Flex layouts, for example: “The Flex layout does not support auto-sizing text frames. If you place auto-sizing text in a Flex layout, the auto-sizing will turn off.” (see Manage Flex Layout conflicts in InDesign for flexible and adaptive layouts.)

Flex Layout Mapping in InDesign

First, the architectural parallels to CSS Flexbox are obvious:

| CSS Flexbox | InDesign Equivalent |

|---|---|

display:flex container |

FlexObject (PageItem implementation with flex behavior) |

| Flex items | PageItem implementations as children |

| Nested flex containers | Recursive FlexObject containment |

| Flex direction, justify, align | FlexObject-specific attributes |

| Dynamic reflow | Automatic child repositioning |

FlexObject is clearly positioned for digital publishing workflows where dynamic, responsive layouts are essential.

Traditional InDesign scheme:

Spread → Group/MSO → [child items, possibly multi-state]

FlexObject pattern:

Spread → FlexObject → [child items with dynamic layout]

FlexObject follows InDesign's pattern for container types by implementing dedicated collection properties:

// Existing patterns document.pageItems // PageItem children (any kind) document.groups // Group containers document.multiStateObjects // MSO containers // etc. // FlexObject additions document.flexObjects // FlexObject containers spread.flexObjects // ...seen from a spread page.flexObjects // ...seen from a page // etc.

An important difference must be noted though: unlike the groups collection, which returns only the direct children of the host object (Document, Spread, etc.), and therefore does not take into account any subgroups located deeper in the hierarchy, the flexObjects collection is exhaustive, meaning that it indexes all Flex objects available under the object in question, including nested FlexObjects. The only entities that might escape flexObjects are those possibly registered in an inactive state in the case of a multi-state configuration (MSO) having FlexObject children.

This peculiarity is also reflected in the generic pageItems collection, which is normally intended to return all direct children (regardless of their type), as opposed to the allPageItems array. Thus, even when a FlexObject is at a deeper hierarchical level, it is still indexed among the pageItems of the host object. If you are designing a script that needs to take nesting structures into account, you must therefore be wary of this architectural inconsistency: given three Flex objects fx1, fx2, fx3 listed in the flexObjects (or pageItems) collection of a certain object obj, you cannot conclude that obj is the direct parent of these three entities; it is possible, for example, that fx3.parent===fx2.parent===fx1.

Note. — To be thorough on the subject of hierarchical relationships, we should add that the collecting properties (flexObjects, pageItems) ignore, as usual, what is happening in the underlying anchored objects. As all InDesign developers know, exploring anchored objects always requires a different approach through text containers. In such cases, an anchored FlexObject (just like any other anchored object) has a Character as its parent.

FlexObject API (Specific Features)

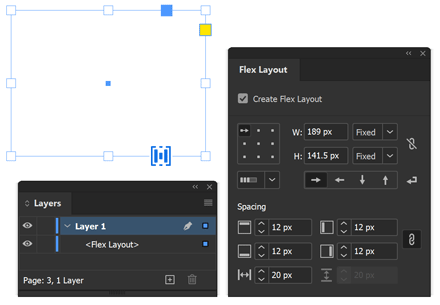

Since FlexObject implements CSS Flexbox-like layout capabilities, it essentially exposes the same API as a Group, to which it adds flex features. Here are the properties and methods that are specific to FlexObject compared to the traditional Group container.

• FlexObject Properties

| NAME | TYPE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| flexWidthMode | enum | The width behavior of the flex container: FlexWidthHeightMode or FlexEnum enum. |

| flexHeightMode | enum | The height behavior of the flex container: FlexWidthHeightMode or FlexEnum enum. |

| flexDirection | enum | The direction of the flex container: FlexDirection |

| flexWrap | enum | Whether flex items are forced onto one line or can wrap onto multiple lines: FlexWrap |

| justifyContent | enum | Defines how the browser distributes space between and around content items along the main-axis: FlexPosition or FlexSpacing enum. |

| alignItems | enum | Defines the default behavior for how flex items are laid out along the cross axis: FlexPosition or FlexEnum enum. |

| alignContent | enum | Aligns a flex container's lines within when there is extra space in the cross-axis: FlexPosition or FlexEnum enum. |

| flexPaddingTop | num/str | Top padding (MeasurementUnit), range: 0–720 pt. |

| flexPaddingRight | num/str | Right padding (MeasurementUnit), range: 0–720 pt. |

| flexPaddingBottom | num/str | Bottom padding (MeasurementUnit), range: 0–720 pt. |

| flexPaddingLeft | num/str | Left padding (MeasurementUnit), range: 0–720 pt. |

| flexGapRow | num/str | Row gap between flex items (MeasurementUnit), range: 0–720 pt. |

| flexGapColumn | num/str | Column gap between flex items (MeasurementUnit), range: 0–720 pt. |

Note. — The Enumeration FlexEnum only provides the FlexEnum.FLEX_AUTO enumerator (i.e. this is an auto enum attribute to be used for properties accepting Auto.) We will not detail the other Enums here, they are well documented and reflect exactly the preferences available in the InDesign Flex Layout panel.

• FlexObject Methods

| NAME | TYPE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| addFlexObject(pgItem) | undef | Add page item to flex container at the end. |

| addPageItemAfter(refItem, pgItem) | undef | Add a page item after the specified page item. |

| addPageItemBefore(refItem, pgItem) | undef | Add a page item before the specified page item. |

| addPageItemAt(positionIndex:num, pgItem) | undef | Add a page item at the specified index. |

| addPageItemAtStart(pgItem) | undef | Add a page item at the start of the container. |

| addPageItemAtEnd(pgItem) | undef | Add a page item at the end of the container. |

All the additive methods above stand out clearly from the API of a Group (which does not have tools for directly inserting existing page items — a problem often encountered by developers and until now solved via temporary MSOs or similar hacks.)

Note. — Another critical point: currently, a FlexObject has no unflex method analogous to Group.ungroup(). In other words, there is no easy way to produce the effect of the Remove Flex Layout command via a script, except by invoking the associated menu action!

Of course, you can create a FlexObject from scratch using the add(…) method of a flexObjects collection. An original aspect of this approach is that it doesn't prevent the declaration of a completely empty FlexObject (that is, without any child elements):

// Testing FlexObjects.add() with no argument: var flx = mySpread.flexObjects.add();

We must also remember that unlike a Group or a MultiStateObject, a FlexObject instantiates a genuine physical container (not just logical), with its own attributes of color, strokes, etc.

Note. — At the time of publication, I have not yet determined the purpose of the flexDescription (string) argument, which is the first optional parameter of the FlexObjects.add(...) method. Despite its obscure name and type, it can be conjectured that this argument might enable loading pre-existing elements when the FlexObject is created (?). I will update this point as soon as I know more.

If you are developing or updating InDesign scripts that use FlexObject containers, a crucial point to keep in mind is that, by definition, child elements lose some degree of freedom regarding their positioning in the layout. Therefore, you should be very careful when using any procedure that controls coordinates, dimensions, or spatial transformations of such objects.

Thinking Flex Objects as Dynamic Groups

The API parallelism with Groups/MSOs reinforces that FlexObject is a container strategy. The collection-based access enables batch operations on all flex containers in a document, consistent scripting patterns across container types, easy migration from static groups to FlexObjects (and vice versa).

The fact that a FlexObject can contain FlexObject children — exactly like any group can contain (sub)groups — enables powerful nested layout patterns:

FlexObject (horizontal layout) ├─ FlexObject (vertical layout) │ ├─ TextFrame │ └─ Image ├─ FlexObject (vertical layout) │ ├─ Button │ └─ Button └─ Rectangle

The innovation is that FlexObject makes this recursion semantically active for your project: each nested FlexObject can specify its own direction, spacing, padding, and alignment properties, creating complex adaptive layouts (function that escaped the Alternative Layout workflows).

Script developers will not be able to ignore the FlexObject component for much longer, as it represents a strategic evolution in InDesign's object model:

— From Absolute to Adaptive Layout: Moving from purely manual positioning toward algorithm-assisted layout while maintaining full geometric control.

— From Static to Dynamic: Enabling containers where, as Adobe states, “the layout adjusts itself” when content changes, which eliminates the need for manual adjustments (think about your DataMerge projects!)

— From Manual to Declarative: Allowing designers to specify layout intent (direction, spacing, alignment) rather than explicit coordinates for every child.